Being medical-surgical nurses, we truly understand the significance of juggling the numerous demands that come with a fast-paced care setting. The constant blaring of alarms has turned into a major hurdle, giving rise to what we now refer to as alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue happens when staff are bombarded with a high number of alarms, many of which don’t require any action. This can lead to desensitization and slower reactions to important alerts [1] [2].

In my latest project, I focused on tackling the problem of non-actionable alarms in an adult general medicine step-down unit. This change not only boosted patient safety but also created a better work environment for the nursing staff.

For context, Cvach (2012) defines non-actionable alarms as any alarm that does not meet the actionable definition, including invalid alarms such as those caused by motion artifact, equipment/technical alarms, and alarms that are valid but non-actionable (nuisance alarms). Actionable alarms are defined as alarms for a clinical condition that either: (1) lead to a clinical intervention, (2) lead to a consultation with another clinician at the bedside (and thus visible on camera), or (3) involve a situation that should have led to intervention or consultation, but the alarm was unwitnessed or misinterpreted by the staff at the bedside (Bonafide et al., 2015).

The Problem: Alarm Fatigue in High-Acuity Units

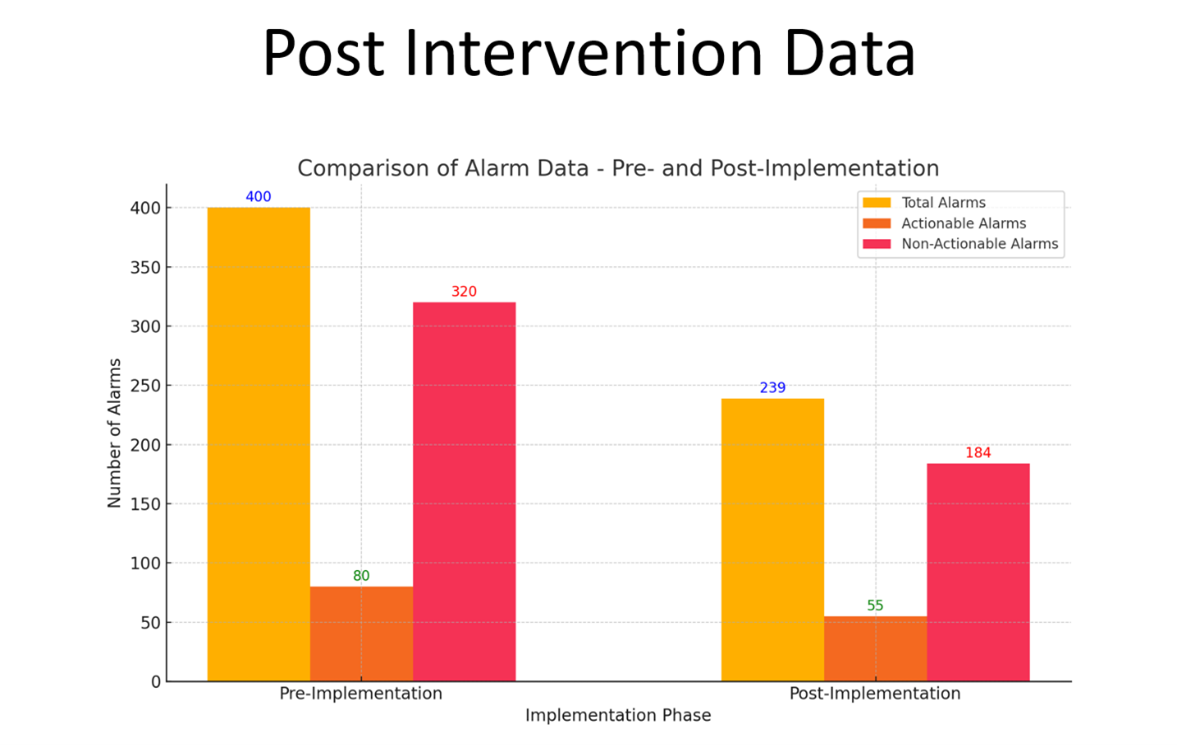

Our 31-bed unit is buzzing with activity, thanks to our dedicated team of 58 registered nurses and nine certified nursing assistants (CNAs). Telemetry monitoring is a vital part of how we care for our patients, ensuring they receive the best attention possible. Typically, during a shift, we keep an eye on about eight to 12 patients through telemetry. On some days, however, most of the patients in our unit require telemetry monitoring. In the initial phase of our project, we took a closer look at six night shifts and found a total of 400 alarms.

Interestingly, a whopping 80% of those — which amounts to 320 alarms — turned out to be non-actionable. Non-actionable alarms often come from false triggers due to patient movement or sensor problems. These distractions pulled staff away from critical alerts, adding to stress and creating inefficiencies in the workflow.

Alarm fatigue isn't just a concern for nurses; it directly impacts patient safety. Studies indicate that too many alarms can slow down reactions to important situations, which might put results at risk [1] [2]. Our team felt the urgency in this message.

The Solution: Targeted Interventions

Reducing non-actionable alarms required a multi-pronged, evidence-based approach. The interventions we implemented were practical and adaptable, focusing on staff engagement and leveraging existing resources.

- Visual Cues With Door Signage

We introduced door signage to visually indicate each patient’s telemetry monitoring status. These simple cues allowed staff to quickly identify monitored patients, reducing unnecessary checks and confusion.

- Customizing Telemetry Parameters

Telemetry alarm thresholds were adjusted based on clinical guidelines and individual patient needs. This step aimed to minimize alarms triggered by insignificant variations, such as minor changes in heart rate.

- Education and Resources

Nurses and CNAs received instructions on accessing Learning Management System (LMS) modules already available on central and bedside telemetry monitors. Additionally, we distributed a guide on reducing alarm fatigue, offering best practices for alarm management and prioritization.

- Continuous Staff Feedback

Throughout the project, staff feedback was solicited to identify challenges and opportunities for improvement. This ensured the interventions remained relevant and effective.

The Results: A Safer, Calmer Environment

After collecting data over six night shifts, we noticed some impressive improvements. There was a notable drop in total alarms, going down by 40% from 400 to just 239 alarms. There was a significant drop in non-actionable alarms, which fell by 42.5% from 320 down to 184. Meanwhile, the percentage of actionable alarms stayed steady, hovering around 20% to 23% of the total alarms.

The results show how effective the interventions have been in tackling alarm fatigue. With fewer non-actionable alarms ringing through the halls, nurses can now focus on the alerts that truly matter. This shift not only enhances patient care but also boosts response times, making a real difference in the day-to-day operations of healthcare.

Lessons Learned and Next Steps

This project really taught me how crucial it is to keep the staff engaged all the time. The feedback we received from nurses and CNAs was incredibly helpful. Their insights guided us in adjusting the interventions, which helped ensure they would be sustainable moving forward. Some staff pointed out that, although the visual cues worked well, it might be beneficial to have extra training on telemetry monitors to improve alarm management even more.

Moving forward, we plan to:

- Maintain the use of door signage and refine their design based on staff suggestions.

- Promote ongoing use of the non-actionable alarm reduction guide and LMS modules.

- Expand the project to other units, sharing resources and gathering feedback to further improve the interventions.

- Explore advanced alarm technologies, such as smart monitors, to build on our success.

Why This Matters

Alarm fatigue isn't just something we're dealing with in our unit; it's a common issue across the field of medical-surgical nursing. Tackling this issue calls for teamwork, innovative thinking, and a strong dedication to ensuring both patient safety and the well-being of staff. We’ve managed to cut down on those pesky non-actionable alarms, and in doing so, we’ve fostered a safer and more supportive atmosphere. This change allows nurses to truly thrive while ensuring that patients get the care and attention they need.

This project showcases how effective teamwork and evidence-based practice can be. The changes might look straightforward, but the effect they have is significant. I'm hoping that our journey encourages others to tackle alarm fatigue and bring about some positive changes in their own work environments.

References

- Bach, T. A., Berglund, L., & Turk, E. (2018). Managing alarm systems for quality and safety in the hospital setting. BMJ Open Quality, 7(3), e000202. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000202

- Bonafide, C. P., Lin, R., Zander, M., Graham, C. S., Paine, C. W., Rock, W., Rich, A., Roberts, K. E., Fortino, M., Nadkarni, V. M., Localio, A. R., & Keren, R. (2015). Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 10(6), 345–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2331

- Cvach, M. (2012). Monitor Alarm Fatigue: An Integrative Review. Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology, 46(4), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.2345/0899-8205-46.4.268

- Sowan, A. K., Tarriela, A. F., Gomez, T. M., Reed, C. C., & Rapp, K. M. (2015). Nurses’ perceptions and practices toward clinical alarms in a transplant cardiac intensive care unit: Exploring key issues leading to alarm fatigue. JMIR Human Factors, 2(1), e3. https://doi.org/10.2196/humanfactors.4196

Content published on the Medical-Surgical Monitor represents the views, thoughts, and opinions of the authors and may not necessarily reflect the views, thoughts, and opinions of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses.