November is recognized as National Hospice and Palliative Care Month. This is a great time to help raise awareness about these services while acknowledging the people who provide this care to patients and their families. Palliative care and hospice are both valuable aspects of patient care; however, there are distinct differences between the two. Unfortunately, there continues to be a lack of understanding of those differences, mainly surrounding palliative care.

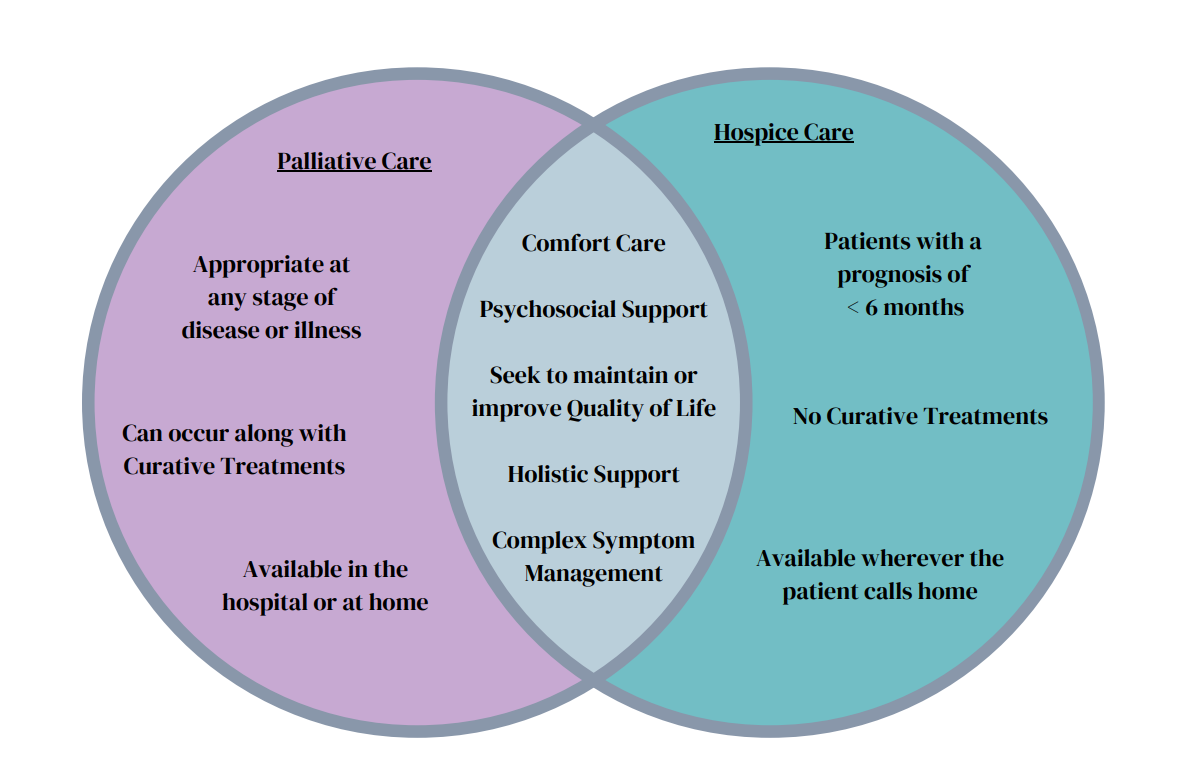

Hospice and palliative care services (PCS) provide patients and families with a wide range of supportive measures aimed at partnering with the primary care team. They both focus on providing comfort, reducing stress and managing symptoms. It’s easy to see why these two service lines are often grouped together in discussions among healthcare workers and consumers.

One of the biggest differences between hospice and PCS is the timing. Hospice care focuses on improving the quality of life for patients at or near the end of life, typically with a prognosis of less than six months. Choosing hospice indicates a decision to end curative treatments and focus on managing symptoms. This allows for the natural progression of the client’s condition. With palliative care, patients can receive the same support and focus on improving quality and comfort, but they can also continue with curative treatments. PCS is appropriate during every phase of treatment for any serious illness, even from the time of initial diagnosis.

The goals of a palliative care team typically include improving symptom management, alleviating psychological distress, and enhancing quality of life. This supplemental care provides an extra layer of support for all parties involved, especially in the early stages of treatment, when there can be a great deal of anxiety, uncertainty, and fear. Delayed referrals to palliative care services can limit the availability of this support for patients. These delays are often rooted in the long-held misconception that palliative care is only appropriate when a patient is terminal or at the end of any viable treatment options. This misconception, coupled with the stigma that surrounds the concept of palliative care, can deter both patients and healthcare professionals from engaging in much-needed discussions about these services.

Coupling palliative care with hospice eliminates many eligible patients from benefiting from these services. Illnesses such as dementia, organ failure, and chronic conditions such as lung disease, HIV, diabetes, and multiple sclerosis all have a high burden of care while not necessarily imminently terminal. Palliative care providers can get involved as early as the time of diagnosis to help patients and their families stay connected with their own goals of care in addition to the curative goals of treatment that are provided by their primary care teams. These patients need support related to their physical, spiritual, and emotional needs, which can be overlooked or even ignored when focused on the disease cure rather than the patient’s care.

One contributing factor to the stigma of palliative care, is often the personal views and biases of healthcare providers. Sometimes, there is an innate fear of patient abandonment by the provider once a referral is made, (Quaidoo et al., 2024). The concern is that the consult will lead to the exclusion of the choices and opinions made by the patient, the family, and the provider themselves. It’s important that palliative care advocates work to address this misunderstanding by speaking up. Using their voice, they can foster more collaborative efforts through the treatment phase of these illnesses rather than waiting to bring them in solely at or near the end. This crucial step can start with education on evidence-based research about the effectiveness of palliative care. The holistic methods of pain management and the inclusion of psychological support work hand in hand with the existing treatments ordered by the primary team. First-hand accounts of how palliative care impacts patients and families through their focus on the physical, emotional, spiritual, social and intellectual needs are powerful and can help clinicians see the true scope and breadth of palliative care. Patients report better quality of life, comfort and a greater ability to engage in their daily lives, and the activities that make life meaningful to them even with the added aspect of illness.

Patient surveys have indicated that a patient’s initial understanding, prior beliefs, and experiences influence their willingness to fully engage with palliative support at any stage other than the end. Patient education is an important action that can help to increase understanding and the utilization of palliative care services. Clinicians - bedside nurses included - can advocate for and help drive these conversations with providers, patients, and families. It’s also worth mentioning that nurses should take time to reflect on their own prior experiences, beliefs, and attitudes on the subject to see if it has impacted their thoughts and actions.

According to the World Health Organization, only 14% of people worldwide who need palliative care currently receive it (WHO, 2024). There are many barriers to making changes, starting with advocacy and information. Locally, nurses can work at their own facility to ensure the benefits of palliative care are included in care plan discussions for patients with serious illness. Advocate for these services with clinical teams. Public communities need help as well. There are many ideas for helping to increase access to these services, which rely on community support. From making health policy changes at the local, national, and global levels to the development of guidelines and tools for clinicians at the bedside, there is no shortage of needs for those who want to help. Groups like the Center to Advance Palliative Care, the National Institute of Health, and so many others have opportunities to learn more about how we can contribute to this cause. Nurses should consider being a part of efforts to reframe conversations around palliative care and bring awareness to services offered and support needed to ensure that PCS is more accessible to anyone who might benefit from it.

Interested in learning more from the author? Listen to the Med-Surg Moments podcast, where Laura serves as a co-host!

References

Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC). (n.d.). CAPC25. Retrieved July 4, 2024, from https://www.capc.org/introtopalliativecarecourse/?gad_source=1%26gclid=EAIaIQobChMI7snuiKmVhwMV1AutBh0q-wXzEAAYASAAEgLnFfD_BwE

Quaidoo, T., Adu, B., Iddrisu, M., Osei-Tutu, F., Baaba, C., Quiadoo, Y., & Poku, C. (2024). Unlocking timely palliative care: Assessing referral practices and barriers at a ghanaian teaching hospital. BMC Palliative Care, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-024-01411-9

World Health Organization. (2020, August 5). Palliative Care [Press release]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

Content published on the Medical-Surgical Monitor represents the views, thoughts, and opinions of the authors and may not necessarily reflect the views, thoughts, and opinions of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses.